Reversing - SabloomText_v6

Today we look at another crackme, SabloomText_v6!

The difficulty is rated at level 4.8 of 6 - I think perhaps it was more like a 4.

I am not going to say anything about it in this section as it would spoil a cool surprise if you want to try it yourself!

Here is the link if you want to try it Sabloom Text 6

Tools used today are x64dbg, PEStudio, F# and C++

(Apologies for the low quality pictures, I messed them up)

First Impressions

As usual, we inspect the binary in PEStudio - it reveals a C++ program with some linked GUI libraries. Nothing striking or out of the ordinary here.

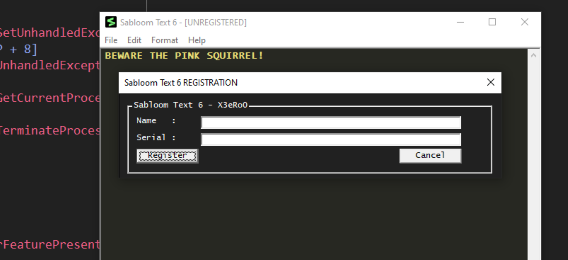

Let’s run the program and see what we have:

A fully functioning text editor, complete with the ability to change the font! It is obviously modelled on Sublime Text, and the problem is of course to work out a username and password to “register” this piece of software!

Looking Inside

Attempting to launch the program with the debugger fails. The IsDebuggerPresent function is imported but it does not seem to be used anywhere. Other usual suspects such as NtQueryInformationProcess OutputDebugString and friends are also not present.

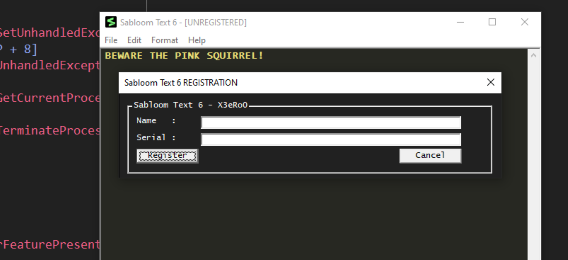

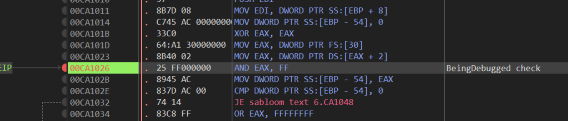

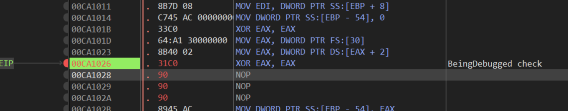

Another common way to detect if the debugger is present is to check the DebuggerPresent flag in PEB block which we can find at [fs:30] + 2. We can use a hardware breakpoint at this location to pause execution when something reads this memory. This leads to the follow piece of anti-debugging code

Which we can neutralise

After this patch, the program is able to start with the debugger. I did discover another similar check later in the code, though it did not cause any trouble.

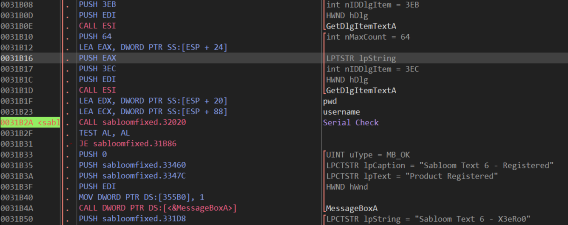

The next task is to find where the username and serial are being checked. To do this I searched for the GetDlgItemText functions, since they are often used to read from input boxes. This led me straight to the following code that performs the serial check:

All easy so far, let’s have a look at the checking function!

The Real Work Begins

First the code checks the username is 6 characters long. At this point it doesn’t do anything else with it. The program then allocates two blocks of memory, sized 0x1081 and 0x37

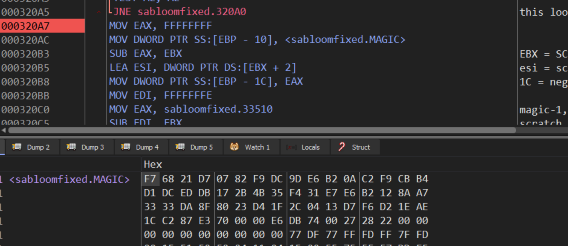

Then follows a ton of code that performs some processing loops of the password and this set of magic numbers, writing the results into one of the allocated memory blocks.

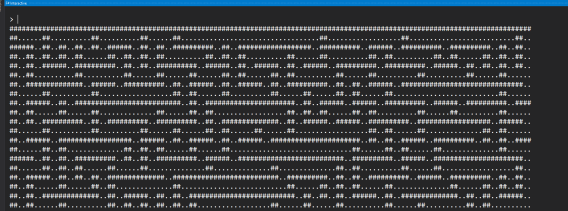

This is a zoomed-out picture of some of the code

As you can see, it is quite long. The code was quite obsfucated and was doing something simple; essentially this:

1 2 3 4 5 |

for (int i = 0; i < 0x37; i++)

{

int index = i % passwordLength;

scratch[i] = password[index] ^ magic[i];

}

|

Several obsfucation techniques have been used. Firstly, instead of a loop with a single index, it uses six different indexes at the same time. They are calcuated by first storing negative offsets from the allocated memory blocks, then restoring them at the point they are needed. It also uses some negative indexes for the array pointers and other things to keep you confused. Knowing now the author likes to obsfucate things, we can expect more in the future.

The next thing the program does is access another set of magic numbers, and for each one it shifts out each bit and stores them in their own byte within the larger section of allocated memory. The code that does this work is also fairly obsfucated using some techniques such as multiple pointers with 3 nested loops and annoying usage of the first 8 / 16 bits of the registers.

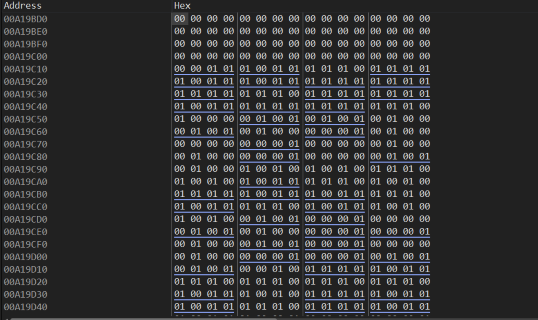

The resulting memory is a large array of 0s and 1s

One thing I did notice whilst reversing this lot is that it seems to treat the magic numbers in groups of 64 each. Before proceeding I decided to re-implement the code in F# and do some analysis / visualisation / playing with it.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 |

type MazeSection =

| Wall

| Passage

| Goal

let encodedMaze = [| |] // too long to show

let magic = [||] // too long to show

// expand into an array of bits

let byteToBits byte = seq { for shift in 7 .. -1 .. 0 -> (byte >>> shift) &&& 0x1 }

// the maze is split into 65 rows of 9 bytes each, where the 9th byte is padding.

// remove the padding bytes and explode each byte into bits

let maze =

encodedMaze

|> Array.mapi(fun i n -> (i+1) % 9, n)

|> Array.filter(fun (i,_) -> i <> 0)

|> Array.map snd

|> Array.collect (byteToBits >> Seq.map(function 0 -> Wall | _ -> Passage) >> Seq.toArray)

maze.[63*64+63] <- Goal // this is the goal at the bottom right (63,63)

// draw maze

let mutable count = 0

for c in maze do

match c with

| Wall -> printf "##"

| Passage-> printf ".."

| Goal -> printf "GG"

if count = 63 then

printfn ""

count <- 0

else

count <- count + 1

|

It’s a maze!

Amazing

This was quite a revelation! At this point I had to dig a bit further into the code to make sure it was actually a maze, and how it worked. Presumably the solution then is some encoded instructions to solving the maze - to do that I would need to know the start and end points of the maze. These turned out to be (1,1) and (63,63) respectively. To encode the instructions we’ll need to understand exactly how the program tries to solve the maze from the decoded password - but first let’s solve the maze!

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 |

maze.[63*64+63] <- Goal // this is the goal at the bottom right (63,63)

let getCell row col =

// if we go out of bounds then return Wall

if row < 0 || row > 64 || col < 0 || col > 64 then Wall else

maze.[row * 64 + col]

type Direction = Up | Down | Left | Right

// we always move in twos

let canMove row col direction =

match direction with

| Up -> getCell (row - 1) col <> Wall && getCell (row - 2) col <> Wall

| Down -> getCell (row + 1) col <> Wall && getCell (row + 2) col <> Wall

| Left -> getCell row (col - 1) <> Wall && getCell row (col - 2) <> Wall

| Right -> getCell row (col + 1) <> Wall && getCell row (col + 2) <> Wall

let getCandidates row col =

[Up;Down;Left;Right]

|> List.filter(fun d -> canMove row col d)

// recursively traverse the maze until we get to the goal

let rec solveMaze row col seen path =

if Set.contains (row,col) seen then None else

if getCell row col = Goal then Some (List.rev path) else

let seen = Set.add (row, col) seen

getCandidates row col

|> List.tryPick(function

| Up -> solveMaze (row - 2) col seen (Up :: path)

| Down -> solveMaze (row + 2) col seen (Down :: path)

| Left -> solveMaze row (col - 2) seen (Left :: path)

| Right -> solveMaze row (col + 2) seen (Right :: path))

let solution = (solveMaze 1 1 Set.empty []).Value

|

Here we use a simple brute-force recursive backtracking maze solver to walk the maze and find a path to the goal. Some details here were extracted from the reverse engineering of the maze algorithm - mainly that it always takes 2 steps in a given direction.

Maze Algorithm

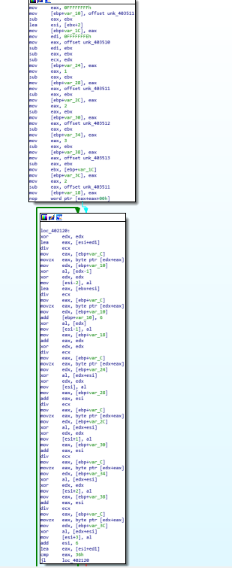

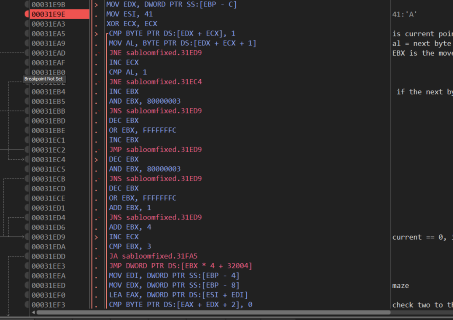

To encode the solution path correctly, we need to know the instruction format. Of course, this was not straight forward and bogged down with some more obsfucated code. Essentially the program takes the decoded password and “explodes out” the bits like it did for the maze itself. Then, it processes the sequence of ones and zeroes in a modulo 3 fashion:

- 0 : Keep moving the same direction as last time

- 11 : Change the current direction + 1 mod 3

- 10 : Change the current direction – 1 mod 3

Where the directions are

- 1 : Right

- 2 : Down

- 3 : Left

- 4 : Up

This is quite clever based on an observation that although there’s four directions, you only ever need three since you never need to go backwards, and three can be encoded in two bits. Notice that if the current byte is not zero, it needs to lookahead one - this makes it a little bit of a pain to generate.

The code itself was quite long and featured a bunch of obsfucation tricks - in addition to the ones already encountered it also used some indirect jumps and other shenanigans:

Here’s a bunch of code that was reading the realtime clock stamp, that was later used to invalidate the password if too long had been taken, in addition to another anti-debugging check. (I think - this code was never a problem)

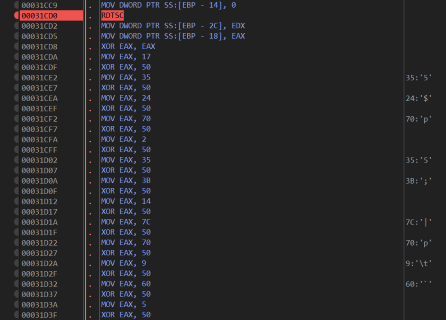

So, to generate the correct solution we first have to take our solution path and generate the correct set of 0s and 1s as per the instruction format above. Then, we need to take those bits and turn them into full bytes. The resulting set of numbers can be XOR’d in sequence with the original set of magic numbers which should yield us the correct key - presumably it must be engineered to result as ascii, otherwise we won’t be able to input it into the text box.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 |

// now we need to encode it back as a bunch of bytes. this is a bit tricky.

// if the direction is the same we emit a 0 bit. If it is different then

// we emit 11 to move to the next direction, and 10 to move to the previous

// direction where the order is 1 = right, 2 = down, 3 = left, 4 = up

// we can do this with some ints but there's only a few cases so we'll just write

// them out explictly

let getBits oldDirection newDirection =

if oldDirection = newDirection then [0] else

match oldDirection, newDirection with

| Right, Down | Down, Left

| Left, Up | Up, Right -> [1;1]

| _ -> [1;0]

let rec generateBytes currentByte currentBit outputBytes inputBits =

match inputBits with

| [] -> outputBytes |> List.rev

| h :: t ->

let by = currentByte ||| (h <<< currentBit)

if currentBit = 0 then

generateBytes 0 7 (by :: outputBytes) t

else

generateBytes by (currentBit - 1) outputBytes t

let bits =

((Right,[]), Right :: solution) // an extra right here, the algo needs an extra 0 to get started

||> List.fold (fun (prev,acc) d -> (d,acc @ getBits prev d))

|> snd

let bytes = generateBytes 0 7 [] bits

let chars = bytes |> List.mapi(fun i y -> (char (magic.[i] ^^^ y))) |> List.toArray

let key = new string(chars)

|

This yields is the key zh3r0{mAzes_w3Re_1nv3nteD_by_EgyptianS_cb3c82b9}zh3r0{

Finishing Up

Inspecting the rest of the code yields some extra tricks as outlined above, with RTSC and more debugger checks. It also looks at the username, where a couple of the characters are explicty hardcoded, and the others reference some of the values from the password. The username is easily determined as X3eR0o, the author of the crackme. And a fantastic job they did of it!